Reporting the Leverhulme Trust residency at the geography department, Durham University

The artist in residency was a unique opportunity to further develop my artistic practice while engaging in a direct dialogue with Professor John Wainwright and other members of the Geographic Department at Durham University. During the period of the residency I had full access to the Durham University’s library and other recourses available to staff. I participated in frequent conversations with the members of the geography department in formal meetings and during their daily informal gatherings and other departmental events. For example, following one such conversation with Professor Wainwright and a visiting professor (Angela Gurnell) about the value of using large wood debris in river management, I had the opportunity to join at a later stage a training session facilitated by the Environment Agency where I gained practical experience in the use of large wood debris and visit a variety of locations in the Berkshire County area where bioengineering techniques are being successfully employed in river management practices.

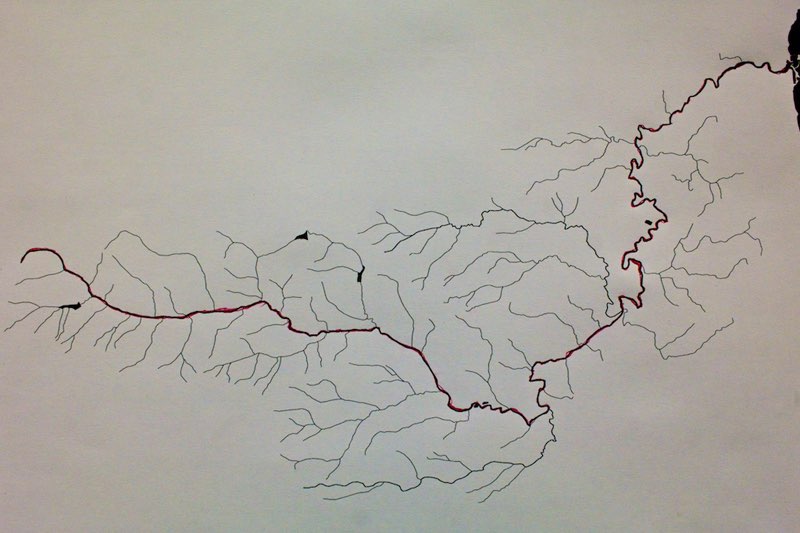

During the first part of the artist in residency, I walked along the River Wear and its catchment area. Between January and June 2015 I covered most of the area while documenting those encounters with the River Wear catchment area. This initial period was important to develop a first-person and direct understanding (phenomenological) of the area while being a valuable source of experiences and ideas for the regular conversations with Professor Wainwright and the other members of the geography department. The walks along the river promoted a wide range of encounters with the landscape and its social realities that resulted in the production of a photographic project (River Wear). The daylong walks allowed for an immersion in the local environment and to understand some of the implications of living in the area, for example: the impact of reduced public transport outside the main cities that limit the movement of local populations or the importance of the industrial revolution’s heritage in the identity of the local populations. The walks also revealed traces of human activities that otherwise would have gone unnoticed, for example: ventilation shafts of disused mines, hidden but fully operational quarries, foresting and farming practices. The photographic work addresses some of those different perspectives about the River Wear and its catchment area, suggesting the existence of various understandings (and uses) of the river rather than a single and unifying relationship (e.g. a farmer at the Wear Head and a fisherman in Sunderland have very different relationships with the river and the environment). Additionally, this period was used to scout for locations where the future artistic interventions in the land and in the river were made. The final location, near the Brancepeth Castle, was found after a series of conversations with members of the geography department, the Wear Rivers Trust and local farmers.

In June 2015, I presented and discussed the project at the Network Ecologies Symposium: Exploring Relations Between Environmental Art, Science & Activism, which took place at the University of Hull, Scarborough Campus, UK. During the presentation I emphasized the variety of perspectives and diversity of relationships with the river found during the various walks and showed some of the photographic work. Also, I discussed some of the ideas regarding the continuation of the project, which at the time were starting to emerge. The diversity of views about a river and how it should be managed is a fairly established idea that is acknowledged in the Water Framework Directive and the presence of various stakeholders discussing the management of the river and its resources (e.g. Durham University, Northumberland Water company, Wear Rivers Trust, the various councils, etc.), Nevertheless, the river and its non-human elements remain without a voice and without agency. At best, a stakeholder with environmental concerns such as the Wear Rivers Trust will attempt to voice the interests of nonhuman beings but their voice remains mute. These thoughts resulted in a conceptual engine for the work that followed in the Brancepeth Beck area: how to listen and produce works of art that will acknowledge the voice and agency of the non-human beings in the area. The emphasis is not on trying to understand the language of a highly complex ecological system that comprehends a wide range of beings and most likely with a variety of different communication systems. Rather, the emphasis is on the action of attempting an impossible endeavour and how that process might raise a variety of valuable considerations regarding existing relationships with the environment and nonhuman beings. This is an experimental idea that acknowledges the limitations of human understandings on language and communication in its attempt to voice and give agency to other nonhuman beings.

The second part of the project, took place in a land near the Brancepeth Castle that is meandered by the Brancepeth Beck and part of the River Wear’s catchment area. The land is part of a working farm but due to its topography, which restricts the access of tractors and other heavy machinery, is in a semi-abandoned state apart the occasional visit by the farm’s sheep but is not cultivated. In this location, I attempted to listen to the environment and reflect on the various scales (or assemblages) that were possible to identify. The assemblages of a bird, tree, sheep or fungi are highly distinct even if they intersect in the same location. The field is only accessibly through the farmland and is closed to the public, requiring a twenty minutes walk across the fields. Although there is a certain level of isolation and distance provided by its semi-abandoned state and restricted accessed, the surroundings of the field were highly present: the sounds of the nearby golf course or the heavy machinery working in close proximity engulfed the land. The field has a rich (hi)story to tell, it was managed as a constituting element of the Brancepeth Castle estate and during the late 18 century was subject to various interventions to implement a highly designed landscape, there are still many elements of a picturesque deer park, which was never fully implemented: the metal fences, small cascades along the beck, fish ponds and how the beck was channelled in certain zones. The human traces in the landscape have been assimilate and in some cases are now an integrated element of the naturalized environment. The anthropocentric epoch (an understanding of the human impact on the environment as a clearly marked geological epoch) was a strong consideration during the initial walks and a fundamental element for the photographic project. Regardless of its recognition as a geological epoch and its starting date, the human impact on the environment (and how Nature is understood or managed) is an undeniable and important element in the definition of contemporary relationships with the environment. That is, a contemporary relationship between a local habitant and its environment is mediated by a variety of factors, which might be from other locations and other times that are accreted and activated during the process of engaging with the environment. The period of time that I spent in the land (Brancepeth Beck) can be understood as a process of accessing and activating some of the existing elements, including elements from the past and other locations, in an attempt to listening to the various nonhuman beings currently present in that specific field.

I made a series of artistic interventions in the land (nonhuman interventions), those were practical experiences which in many cases no longer exist. Those actions were part of an attempt to establish a dialogue with the environment in the Brancepeth Beck: making initial questions (an intervention in the land or water) that could have an answer (a visible reaction to the initial intervention). For example, a small twig placed on the water creates the conditions for the floating foam (invisible pollution from an upstream sewage works) to become trapped, accumulating and becoming visible. Or, a series of cuts made in an old oak tree, which had fallen a few years ago, contributing to the expansion of existing fungi and the appearance of various mushrooms. Most of the interventions have disappeared, washed away by the winter rains, collapsed by the strong winds or as the result of the interaction with the various living beings that co-exit in the field but their disappearance or transformation is a valuable part of that attempt to listening to the environment. Their integration or destruction is part of the answer. This experimental period in the field was of a significant importance even without an obvious final product. There is a variety of documentation relevant for future work but the enaction of the reasoning process should be understood as a phenomenological process that needs to take place in the field in the attempt of listening to the environment. This process requires an embodied mind in the world; the physical relations (including perceptual and cognitive) with the environment need to be acknowledged. In this context, a final visit (workshop) with students and staff will be made in late April 2016 to understand some of the limitations of promoting the enaction of the reasoning process by different audiences. This workshop was initially scheduled to take place during residency but was postpone due to the weather conditions.

January 2016